12 years ago Alyssa and I spent an amazing Easter in the Tanami Desert in North Western, Central Australia.

12 years ago Alyssa and I spent an amazing Easter in the Tanami Desert in North Western, Central Australia.

We were invited to an Aboriginal community called Willowra, to celebrate Easter with the locals, the Walpiri tribe.

Willowra station is the centre of the Walpiri homeland and is a couple of hundred kilometers from Alice Springs, the nearest major settlement in Central Australia and home to Alyssa and I at the time.

While we were at Willowra we had the privilege of meeting Eddie, one of the Willowra elders. I still remember him clearly, a weathered old man in red stained, well worn jeans and a faded Elvis tee shirt. Eddie's english was broken and difficult to understand, and our host, a local Baptist pastor familiar with the local language, was able to translate some of his story for us.

Apparently Eddie was the first among his tribe, as a 12 year old boy, to see white people. He remembers hiding as a horse drawn drey pulled into the good grazing lands surrounding Willowra and he and his young friends warily made first contact with these strange, white people.

Eddie and his family and tribe went on to become Christians. So Easter at Willowra was a special affair, celebrated in traditional Aboriginal fashion.

Eddie said he was thankful to missionaries who came and brought them the gospel. He said it was really just a reintroduction to the Creator God. His people, he said, had once known God well, but somewhere along the way the knowledge was lost - they forgot his name, and who he really was, even though they still acknowledged him at certain times of the year and in certain ceremonies. Yet the white missionaries restored the lost knowledge and through them they also came to know Jesus Christ as their Saviour.

At about 5 o'clock on Good Friday afternoon the men and the women split into two separate groups and began to apply their corroboree dress. They smeared their bodies in red ochre, the women applying white crosses to their arms and breasts and the men, gird only in red loin clothes, applied a fluffy substance, white and brown, to their bodies. And as the sun set they began to dance and sing.

To an outsider like me their language and dance was mesmerising. Even though I couldn't understand the words they were singing it was easy to get the meaning of their performance. It was a deeply moving retelling of the 2000 year old story of the betrayal and crucifixion of Christ in traditional Aboriginal form - a purlapa or corroboree.

My point in telling you this story of our Easter at Willowra is this: as foreign as the Aboriginal Easter celebrations were to Alyssa and I (even though we have lived in this country all our lives), the original, Jerusalem crucifixion is just as foreign. Yet for us as Western followers of Jesus or for our brothers and sisters at Willowra, the message, the power of the event is not lost. The crucifixion transcends culture and time and has power and meaning and a message, no matter who we are or where we are in this amazing world.

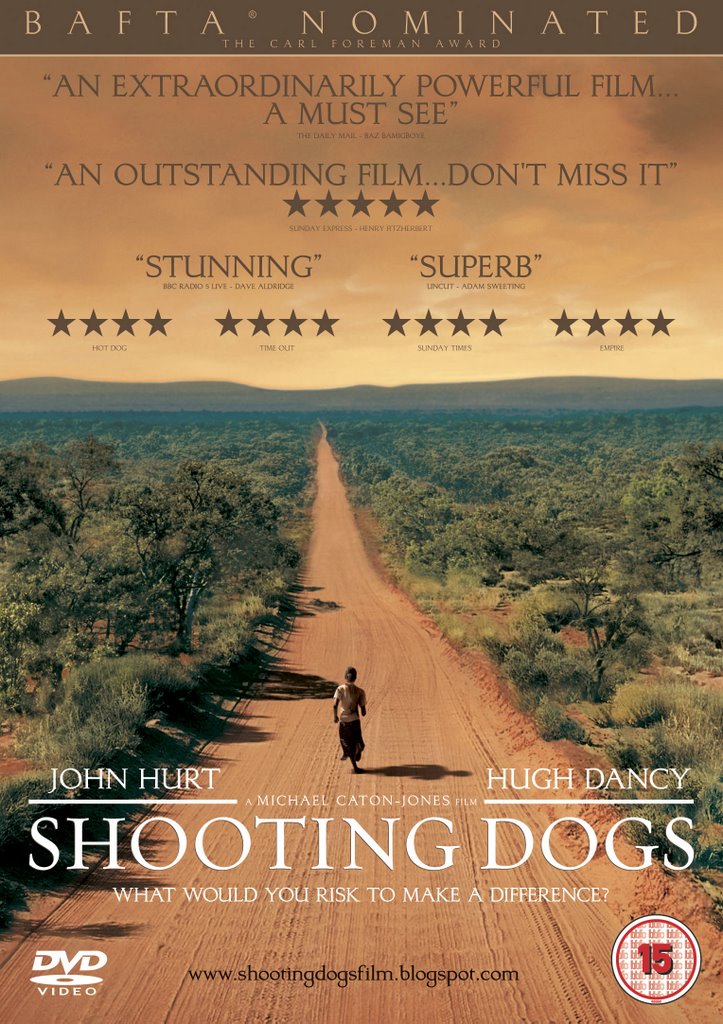

Whether we are Australian aboriginals in the Tanami desert, or Indians in Mumbai, or Africans in Rwanda the cross reminds us off the greatest gift humanity has ever received.

Even though there have been many crosses throughout history - thousands have died nailed to Roman crucifixes, soldiers have fought and killed behind crosses emblazoned on shields and under banners baring the symbol - the real significance of the cross of Calvary isn't the cross itself, rather it relates directly, solely to the one who was nailed upon it.

If Jesus was just another criminal, crucified like thousands of others before and after him, then the cross would have no significance at all. It would only be remembered as a symbol of Roman brutality, a historical showpiece or curiosity, much like the hangman’s gallows in an old prison. Enough to send a shiver down your spine but nothing more.

Yet the cross of Christ is not just an ordinary symbol of death – simply because Christ was no ordinary person, no ordinary Jew, no ordinary prisoner.

His death was significant – not just in a Jewish world, or a Greco-Roman world, not just 2000 years ago. But significant in such a way that the echoes of the crucifixion continue to reverberate through all history and into every culture, race, tribe and nation. Christ’s death speaks to us all, no matter what our background or ethnicity. In this way it is unique among all the world religions.

And, while it is and always will be a symbol of death (just look at the numerous crosses marking the places of fatal car accidents), it is also a symbol of love and life.

Philip Yancey writes of this love and the decision faced by the world in accepting, or rejecting it;

Thieves crucified on either side of Jesus showed two possible responses. One mocked Jesus' powerlessness: A Messiah who can't even save himself? The other recognised a different kind of power. Taking the risk of faith, he asked Jesus to "remember me when you come into your kingdom." No one else, except in mockery, had addressed Jesus as a king. The dying thief saw more clearly than anyone else the nature of Jesus' kingdom.

In a sense, the paired thieves present the choice that all history has had to decide about the cross. Do we look at Jesus' powerlessness as an example of God's impotence or as proof of God's love? The Romans, bred on power deities like Jupiter, could recognise little godlikeness in a crumpled corpse hanging on a tree. Devout Jews, bred on stories of a power Jehovah, saw little to be admired in this god who died in weakness and in shame.

... Even so, over time it was the cross on the hill that changed the moral landscape of the world ...

The balance of power shifted more than slightly that day on Calvary because of who it was that absorbed the evil. If Jesus of Nazareth had been one more innocent victim, like King, Mandela, Havel, and Solzhenitsyn, he would have made his mark in history and faded from the scene. No religion would have sprung up around him. What changed history was the disciples' dawning awareness (it took the Resurrection to convince them) that God himself had chosen the way of weakness. The cross redefines God as One who is willing to relinquish power for the sake of love. Jesus became, in Dorothy Solle's phrase, "God's unilateral disarmament".

Power, no matter how well-intentioned, tends to cause suffering. Love, being venerable, absorbs it. In a point of convergence on a hill called Calvary, God renounced the one for the sake of the other. The Jesus I never knew, 1995, pp.203-205.

Yancey presents us with the

challenge, the love, the true power of the crucifixion.

How will we view the cross of Calvary - or more importantly, how will we view the One who was executed upon it?

The Calvary crucifixion is a transcendent event – it truly does transcend time, and culture and religion. The fact that this weekend, all over this planet, people will be gathering to remember and celebrate this single event is proof of its transcendence.

So let us, this Good Friday, this Easter and every day of every week of every year, also remember the significance of the cross of Calvary and the death of the One who was nailed upon it, in freeing us from death and judgment and providing for us the opportunity to accept the love of the living God, in the name of His Son, Jesus Christ.

And as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, so must the Son of Man be lifted up, that whoever believes in him may have eternal life.

For God so loved the world, that he gave his only Son, that whoever believes in him should not perish but have eternal life. For God did not send his Son into the world to condemn the world, but in order that the world might be saved through him.

Whoever believes in him is not condemned, but whoever does not believe is condemned already, because he has not believed in the name of the only Son of God.

And this is the judgment: the light has come into the world, and people loved the darkness rather than the light because their deeds were evil.

For everyone who does wicked things hates the light and does not come to the light, lest his deeds should be exposed. But whoever does what is true comes to the light, so that it may be clearly seen that his deeds have been carried out in God.

This is the Word of the Lord.